Early Years

Pavlos Melas was born in Marseilles, France, on March 29, 1870. He was one of the seven children of mainland merchant Michael Melas and Helen Vuccina (daughter of a wealthy Cephalonian trader from Odessa). The origin of his family was from Parakalamamos Pogoniou of Epirus, where the ruins of the family tower still survive.

In 1874 his family settled in Athens and resided in a building on Panepistimiou Street (which today is the headquarters of the Athenian Club).

At that time the main national and political ideological current in Greece was the Great Idea, the expansion of the Greek state’s borders to include Greek countries that were under foreign rule.

Michael Melas shared this vision and spent a significant portion of his personal fortune on it. In 1878 he became a treasurer of the National Defense, an organization which supported alienated movements in Epirus and Crete. He dealt with politics, was elected a deputy of Attica in 1890 and the mayor of Athens the following year. In such an ideological climate young Pavlos was brought up.

University Years & Marriage

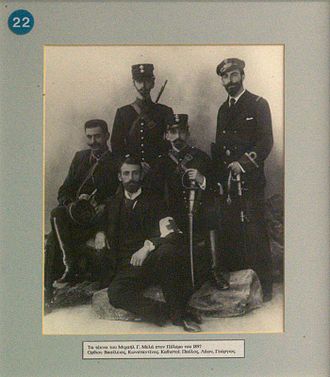

In 1885 Melas completed his secondary education and in September, 1886, began his five-year training at the Hellenic Army Military School in Piraeus, where he graduated in August, 1891, as a lieutenant in the 18th Artillery.

At the same time he met Natalia Dragoumi, daughter of politician and future Prime Minister Stefanos Dragoumis and sister of Ion Dragoumis. Stefanos Dragoumis was also a fiery patriot and had given his children the same ideals.

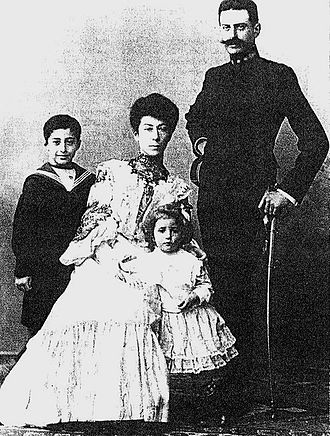

Pavlos and Natalia were married in October, 1892 and had two children: Michael Melas in 1895 and Zoe Mela in 1897.

Despite great differences in character, Natalia admired the boyisness that characterized Melas and supported him in his decisions, while Melas respected her sensible advice and regretted not feeling worthy enough to play the role of her patron.

With his children, who were a source of satisfaction, he did not hesitate to behave with love and with unshaken childlike behaviour even before others.

National Company and the War of 1897

In August 1894, Melas along with 85 other officers participated in the destruction of the Acropolis newspaper offices, which, after the ruthless beating of a citizen by three officers, had published a front-page article denouncing their authoritarianism and questioned the usefulness of the officers’ corps. The soldiers were taken to the military court, but their pre-trial detention order remained unanswered and they were acquitted at the military court.

In November, fourteen of them founded the National Society, among which the first members were Melas, with a registration number 25.

Melas was one of the most active officers who were members of the National Society, with regard to the establishment of new subdivisions in the province and ensuring their seamless communication with its leadership.

On February 12, 1897, Melas served as a guard at the University of Athens when he was invited to return with his men to the artillery barracks. Under pressure from the National Society and against the will of the Great Powers, the Greek government had decided to send expeditionary troops to Crete to support the revolution there.

Disappointed, Melas learned that his unit was not included in the expedition. The next day, however, it was announced that his lowland fire, under the command of Prince Nicholas, would go to Larissa.

On February 16, 1897, the unit departed by ferry from Piraeus (through Chalkida) and arrived by train from Volos to Larissa. Covering his superiors, Melas was responsible for moving a 55-wagon train from Volos to the Greek-Ottoman national border of the National Society that intended to invade the Ottoman Empire to provoke war. The failed invasion of Greek mischief in Macedonia on April 9 gave the Ottoman government the cause it was seeking for a declaration of war. On April 18, diplomatic relations between the two countries were suspended and the war was declared.

In his diaries Melas appears excited by the start of hostilities. However, the rapid negative turn of events, the irregular retreat of the Greek army and the evacuation of Larissa disappointed Melas.

On May 18, with the news of his father’s telegram he became ill with a high fever and the doctor sent him to Lamia and then to the Thessaly Floating Hospital, where his wife was a volunteer nurse. Together they returned to his family home in Athens, where he recovered for a week and then requested and returned to Lamia. He would soon return to Athens because of the illness of his father, who died on June 17. In his father’s coffin Melas vowed to offer his life to the nation.

In January 1899, Melas became a member of the board of directors of the National Society, which dissolved itself in December 1900 following a general outcry over the defeat of 1897 and a dispute with the government over the management of its funds.

However, following a proposal by Melas and Nikolaos Politis, it was decided that the Board of Directors of the Company would continue to discuss national issues “suggesting similar solutions to the respective Government”.

Involvement in Macedonian Affairs

Mourning the outcome of the war of 1897, Melas was heavily involved in Macedonian affairs, which were of great importance to the Dragoumis, a family of politicians, all of whom were actively involved in the matter. Around the Dragoumi family and at the initiative of Mela’s brother-in-law, Ionas, an organization was formed to defend Hellenism in Macedonia. The idea was widely adopted by young officers and officers who had been members of the National Society.

Officers serving in the Army Cartographic Service carried weapons to Macedonia’s frontier into the hands of people such as the Metropolitan of Kastoria German Karavangelis. In November 1902, Ion Dragoumis was appointed vice-consul at the Monastery. From there, Dragoumis maintained correspondence with Melas, whom he informed by letter, asking him to send weapons, money, and recommended the acquisition of European newspapers.

In January 1903, Dragoumis informed Melas of the imminent establishment and aims of the Macedonian Committee of the “few people, rich and good” and rejected “sickness” as constitutional parliament, but only accepted parliament “Provincial” and not “national issues”, in order not to “make people angry if they take away their vote”.

Although Melas himself, like Stefanos Dragoumis, did not become a member of the Komitatos, they nevertheless cooperated with his members using their own network. At the request of the Metropolitan of Kastoria, Melas organized in May 1903 with the help of Lieutenant George Tsondos and with the sponsorship of Louisa Riankour the expedition to Karavangeli of eleven Cretan mercenaries.

These Cretans either escorted the bishop’s armed forces to perform divine service in outer villages or attacked groups of EMEA militias and, with Ilinden’s uprising, rebel peasants, until being sent by Karavagelis, in August, to Melas and Stefanos Dragoumis. In October, Ion Dragoumis wrote to Melas to be ready to move militarily, either against the Bulgarians in Macedonia or to seize power in Greece.

Armed action

Kotas’s capture by the Ottoman authorities, probably after the betrayal of his former associates (German Karavangelis most likely), in June 1904, deprived the Greek side of its action in the region of Korestia. On August 14, shortly after his return from Kozani and with the intervention of Prime Minister George Theotokis, Melas was appointed by the Macedonian Commiton to head all the troops operating in the area of Monastiri and Kastoria.

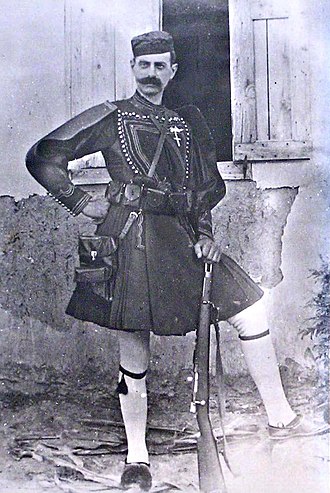

Melas departed with some secrecy four days later for his third tour of Macedonia accompanied by Pyrzas and three Cretans. In Larissa, Melas was hosted by Lieutenant Haralambos Lufa who, according to a letter sent by Melas to his wife, asked him to take his picture. Melas agreed and was photographed armed on August 21 by photographer Gerasimos Dafnopoulos.

On the night of the 27th of August, Pavlos Melas under the operational name “Zezas” and with an armed body of about 35 men, Cretans and Macedonians alike, crossed the Greek-Ottoman border and invaded the Macedonian territories near Ostrovo.

Mela’s armed body was home to local thieves and Cretans of similar occupations, who moved and acted like thief groups. Crossing the border, Melas tried to adopt the thief’s attitude, expelled the officer’s uniform and chose the dulama as his permanent garment, thereby gaining the respect of his men.

On August 30th, robber Thanasis Vagias (hired by Melas as a quide), defected and then handed Melas‘ body to the Ottomans. For more than a week Mela’s body wandered around the Samarina area, mounting at night, often in the rain, to pass unnoticed.

On September 5, after many days of confronting the local population’s suspicion, Melas and his companions reached the village of Zansko, where they were assisted and provided with by a trusted man. On September 7, they crossed Aliakmon river and with several stops in the Greek-speaking Patriarchal Kostaratsi (where they stayed for three days receiving requests for help from neighboring villages) arrived in the Albanian-speaking patriarchal village of Lechovo, on September 13.

There they met the local thief Zisis Dimoulios, who with the permission of the Ottoman authorities, maintained a body of nine men and worked for the patriarchal interests. With Pyrza, Melas debated the need to avenge the murder of the priest of the Slavonic-speaking village of Strabeno, who was assassinated by Komitas in November 1901.

For Melas and other Greek officers headed by the free Greek kingdom in Macedonia, the tacit refusal of Slav-speaking peasants to recognize their Bulgarian leader as Exarchate instead of the Ecumenical Patriarch was proof of their greekness. Melas regarded the Slav-speaking peasants as Greek as the Greek-speaking Cretans who accompanied him and believed that they had been alienated as a result of foreign domination, emigration, and a lack of Greek education.

He called them “Macedonians”, meaning that they were residents of Macedonia, and their language was “Macedonian” and considered them to be like the rest of the patriarch’s flute. Realizing the difficulty of identifying the peasants with national concepts, Melas explained to his men that the basis of the struggle they were to carry out was religion, which was offended by Bulgarian action. He chose the cross as his seal and the inscription “Nieto Nika”, symbols understood by the villagers he intended to associate.

On September 15, Melas launched his first operation. He arrested an elderly man and two children, aged 8 and 15, outside Stremben, and then the 15-year-old’s wanted father. Early in the evening the body invaded the village and arrested another wanted villager. He finally decided not to kill the two wanted men on the condition that they would go to the Greek Metropolis and declare submission to the Metropolitan there.

Mela’s lenient attitude caused the patriarchal village to look for retribution for the acts of violence perpetrated by the Bulgarian armed forces in previous years.

Despite the guerrillas’ doubts about Mela’s abilities as a military, they recognized his moral purity and courtesy and thus he enjoyed their appreciation.

On September 17, Melas attempted to stage an attack on the village of Aetozi, as it was a center for exterior separatists, but Zisi’s reluctance to cooperate with Lechovo changed his plans. Not having any men who knew the area and not being able to follow the elusive movements of the exterior bodies, he was forced to turn to individuals and decided to attack the neighboring village of Prekopana.

There he surrounded the local population and demanded that they declare allegiance to the Greek Metropolitan and ask for the mission of a new priest and teacher. To make his threat believable, he took with him the ex-teacher and the ex-priest and his associates executed them just outside the village.

He then headed to the village of Belkameni, where they were greeted by Greek villagers in secresy. The following afternoon the body entered the village and forced the Romanian teacher to flee. Early in the evening the body was directed to hit the slavic-speaking village of Neret.

The next day, however, their plans were thwarted when they realized that the village had a significant Ottoman army. Mela’s co-worker, Filippos Kapetanopoulos, was fatally injured during the unrest.

From Neret Mela’s body headed to patriarchal Lechovo and then to Negovani where it stayed for several days due to uninterrupted rainfall. During his stay in Negovani Melas organized the defense of the wider area.

They were met there on September 30 by priests from the Vlach village of Nevesca, who provided them with food and clothing, and Karalibanos with about forty men, causing Mela’s body to exceed the number of 70 in number.

Fragmented into four groups under Karalivanos, Giovanni, Poulakas and Pyrzas, the large body forced many komitas to flee their villages.

Death

Having organized the defense of the villages of Kastoria, Melas intended to let about fifty men to control the area and for himself to pass through Zelovo and Pisoderi to the area of Megarovo and the Monastery, to expel the guerrillas from there and organize their defense for the winter.

On October 9th, he received aid from Greece and two days later a force of 60 men attacked planned members of komitas in the Neret community, where he was notified that three gangs of hijackers were hiding by the son of the murdered village priest.

The operation was fruitless and during the retreat the Greek troops were attacked by komitas, but managed to escape. After a failed raid on Neret, Melas wal left with half his men, stayed overnight in Vichy [95] and sent a message to Cyrus and Caudis on October 14 to meet near Statista.

Despite Pyrza’s objection that it would be safer not to enter the Statista, as it was a passage of the Turkish forces which regularly moved from Zelovo to Konoplati, Melas insisted on entering the village.

There they were welcomed to the village by local lords and by Dina (or Dine) Stergiou, a 24-year-old former komita and member of Mitros Vlacho’s team.

Dina would lead Mela’s body to the meeting place with Caudis and Cyrus on October 14 and help Melas divide his men in five houses. On the afternoon of October 13, when informed that an Ottoman extract had departed from Konoplati, Melas was not worried, knowing that it was not a Turkish policy to deliberately attack Greek groups, who relieved them of the task of pursuing Komitas.

However, the extract had been mobilized after receiving a misleading letter written in Greek by the outlaw komita Mitros Vlachos and sent by a villager, which wrote that he was in Statista himself, estimating that the Turkish lord would come to receive the payment for turning him in, all the while causing Mela’s death

On October 13, the village was surrounded by an Ottoman army of 150 men and clashes broke out. The next day’s dawn found Melas dead under unspecified conditions.