Early Life

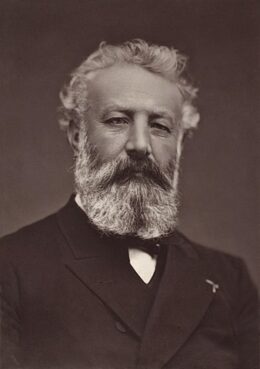

Jules Gabriel Verne was born on 8 February 1828, on Île Feydeau, a small artificial island on the Loire River within the town of Nantes, in No. 4 Rue Olivier-de-Clisson, the house of his maternal grandmother Dame Sophie Marie Adélaïde Julienne Allotte de La Fuÿe.

His parents were Pierre Verne, an attorney originally from Provins, and Sophie Allotte de La Fuÿe, a Nantes woman from a local family of navigators and shipowners with distant Scottish descent.

In 1829, the Verne family moved to No. 2 Quai Jean-Bart, where Verne’s brother Paul was born the same year. Three sisters, Anne (1836), Mathilde (1839), and Marie (1842) would follow.

In 1834, Verne was sent to boarding school at 5 Place du Bouffay in Nantes. The teacher, Madame Sambin, was the widow of a naval captain who had disappeared some 30 years before.

Madame Sambin often told the students that her husband was a shipwrecked castaway and that he would eventually return like Robinson Crusoe from his desert island paradise.

The theme of the robinsonade would stay with Verne throughout his life and appear in many of his novels, including The Mysterious Island (1874), Second Fatherland (1900), and The School for Robinsons (1882).

In 1836, Verne went on to École Saint‑Stanislas, a Catholic school suiting the pious religious tastes of his father. Verne quickly distinguished himself in mémoire (recitation from memory), geography, Greek, Latin, and singing. In the same year, Pierre Verne bought a vacation house at 29 Rue des Réformés in the village of Chantenay (now part of Nantes) on the Loire River.

In his brief memoir Souvenirs d’enfance et de jeunesse (Memories of Childhood and Youth, 1890), Verne recalled a deep fascination with the river and with the many merchant vessels navigating it.

He also took vacations at Brains, in the house of his uncle Prudent Allotte, a retired shipowner, who had gone around the world and served as mayor of Brains from 1828 to 1837.

Verne took joy in playing interminable rounds of the Game of the Goose with his uncle and both the game and his uncle’s name would be memorialized in two late novels (The Will of an Eccentric (1900) and Robur the Conqueror (1886), respectively).

Legend has it that at the age of 11 Verne secretly procured a spot as cabin boy on the three-mast ship Coralie with the intention of traveling to the Indies. The evening the ship set out for the Indies, it stopped first at Paimboeuf where Pierre Verne arrived just in time to catch his son and make him promise to travel “only in his imagination”.

In 1840, the Vernes moved again to a large apartment at No. 6 Rue Jean-Jacques-Rousseau. In the same year Verne entered another religious school, the Petit Séminaire de Saint-Donatien, as a lay student.

His unfinished novel Un prêtre en 1839 (A Priest in 1839), written in his teens and the earliest of his prose works to survive, describes the seminary in disparaging terms.

From 1844 to 1846, Verne and his brother Paul were enrolled in the Lycée Royal (now the Lycée Georges-Clemenceau) in Nantes. After finishing classes in rhetoric and philosophy Jules took the baccalauréat at Rennes and received the grade “Good Enough” on 29 July 1846.

By 1847, Verne had taken seriously to writing long works in the style of Victor Hugo, beginning Un prêtre en 1839 and seeing two verse tragedies, Alexandre VI and La Conspiration des poudres (The Gunpowder Plot), to completion.

However, his father took it for granted that Verne, being the firstborn son of the family, would not attempt to make money in literature but would instead inherit the family law practice.

In 1847, Verne’s father sent him to Paris, primarily to begin his studies in law school and secondarily to distance him temporarily from Nantes. His cousin Caroline, with whom Jules was in love, was married on 27 April 1847, to Émile Dezaunay, a man of 40, with whom she would have five children.

After a short stay in Paris, where he passed first-year law exams, Verne returned to Nantes for his father’s help in preparing for the second year. While in Nantes, he met Rose Herminie Arnaud Grossetière, a young woman one year his senior and fell intensely in love with her.

He wrote and dedicated some thirty poems to her, including La Fille de l’air (The Daughter of Air), which describes her as “blonde and enchanting / winged and transparent”. His passion seems to have been reciprocated, at least for a short time, but Grossetière’s parents frowned upon the idea of their daughter marrying a young student of uncertain future and married her instead to Armand Terrien de la Haye, a rich landowner ten years her senior, on 19 July 1848.

The sudden marriage sent Verne into deep frustration. He wrote a hallucinatory letter to his mother, apparently composed in a state of half-drunkenness, in which under pretext of a dream he described his misery.

This requited but aborted love affair seems to have permanently marked the author and his work, as his novels include a significant number of young women married against their will (Gérande in Master Zacharius (1854), Sava in Mathias Sandorf (1885), Ellen in A Floating City (1871), etc.), to such an extent that the scholar Christian Chelebourg attributed the recurring theme to a “Herminie complex”.

The incident also led Verne to bear a grudge against his birthplace and Nantes society, which he criticized in his poem La sixième ville de France (The Sixth City of France).

Studying in Paris

In July 1848, Verne left Nantes again for Paris, where his father intended him to finish law studies and take up law as a profession. He obtained permission from his father to rent a furnished apartment at 24 Rue de l’Ancienne-Comédie, which he shared with Édouard Bonamy, another student of Nantes origin.

Verne arrived in Paris during a time of political upheaval: the French Revolution of 1848. In February, Louis Philippe I had been overthrown and had fled and on 24 February, a provisional government of the French Second Republic took power, but political demonstrations continued, and social tension remained.

In June, barricades went up in Paris and the government sent Louis-Eugène Cavaignac to crush the insurrection. Verne entered the city shortly before the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte as the first president of the Republic, a state of affairs that would last until the French coup of 1851.

In a letter to his family, Verne described the bombarded state of the city after the recent June Days uprising but assured them that the anniversary of Bastille Day had gone by without any significant conflict.

Verne used his family connections to make an entrance into Paris society. His uncle Francisque de Chatêaubourg introduced him into literary salons and Verne particularly frequented those of Mme de Barrère, a friend of his mother’s.

While continuing his law studies, he fed his passion for the theater by writing numerous plays. Verne later recalled: “I was greatly under the influence of Victor Hugo, indeed, very excited by reading and re-reading his works. At that time I could have recited by heart whole pages of Notre Dame de Paris, but it was his dramatic work that most influenced me.”

Another source of creative stimulation came from a neighbor, the young composer, Aristide Hignard, with whom Verne soon became good friends, and for whom Verne wrote several texts to set as chansons.

During this period, Verne’s letters to his parents primarily focused on expenses and on a suddenly appearing series of violent stomach cramps,the first of many he would suffer from during his life. Rumors of an outbreak of cholera in March 1849 exacerbated these medical concerns.

Yet another health problem would strike in 1851 when Verne suffered the first of four attacks of facial paralysis. These attacks, rather than being psychosomatic, were due to an inflammation in the middle ear, though this cause remained unknown to Verne during his life.

In the same year, Verne was required to enlist in the French military but the sortition process spared him, to his great relief.

He wrote to his father: “You should already know, dear papa, what I think of the military life, and of these domestic servants in livery. … You have to abandon all dignity to perform such functions.”

Verne’s strong antiwar sentiments, to the dismay of his father, would remain steadfast throughout his life.

Though writing profusely and frequenting the salons, Verne diligently pursued his law studies and graduated with a licence en droit in January 1851.

Literary debut

Thanks to his visits to salons Verne came into contact in 1849 with Alexandre Dumas through the mutual acquaintance of a celebrated chirologist of the time, the Chevalier d’Arpentigny.

Verne became close friends with Dumas’ son, Alexandre Dumas fils and showed him a manuscript for a stage comedy, Les Pailles rompues (The Broken Straws).

The two young men revised the play together and Dumas, through arrangements with his father, had it produced by the Opéra-National at the Théâtre Historique in Paris, opening on 12 June 1850.

In 1851, Verne met with a fellow writer from Nantes, Pierre-Michel-François Chevalier, the editor-in-chief of the magazine Musée des familles (The Family Museum).

Pitre-Chevalier was looking for articles about geography, history, science, and technology, and was keen to make sure that the educational component would be made accessible to large popular audiences using a straightforward prose style or an engaging fictional story.

Verne, with his delight in diligent research, was a natural for the job. Verne first offered him a short historical adventure story, The First Ships of the Mexican Navy, written in the style of James Fenimore Cooper, whose novels had deeply influenced him.

Pitre-Chevalier published it in July 1851 and in the same year published a second short story by Verne, A Voyage in a Balloon (August 1851). The latter story, with its combination of adventurous narrative, travel themes, and detailed historical research, would later be described by Verne as “the first indication of the line of novel that I was destined to follow”.

Dumas fils put Verne in contact with Jules Seveste, a stage director who had taken over the directorship of the Théâtre Historique and renamed it the Théâtre Lyrique. Seveste offered Verne the job of secretary of the theater, with little or no salary attached.

Verne accepted, using the opportunity to write and produce several comic operas written in collaboration with Hignard and the prolific librettist Michel Carré.

To celebrate his employment at the Théâtre Lyrique, Verne joined with ten friends to found a bachelors’ dining club, the Onze-sans-femme (Eleven Bachelors).

For some time, Verne’s father pressed him to abandon his writing and begin a business as a lawyer. However, Verne argued in his letters that he could only find success in literature. The pressure to plan for a secure future in law reached its climax in January 1852, when his father offered Verne his own Nantes law practice.

Faced with this ultimatum, Verne decided conclusively to continue his literary life and refuse the job, writing: “Am I not right to follow my own instincts? It’s because I know who I am that I realize what I can be one day.”

Meanwhile, Verne was spending much time at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, conducting research for his stories and feeding his passion for science and recent discoveries, especially in geography.

It was in this period that Verne met the illustrious geographer and explorer Jacques Arago, who continued to travel extensively despite his blindness (he had lost his sight completely in 1837).

The two men became good friends and Arago’s innovative and witty accounts of his travels led Verne toward a newly developing genre of literature: travel writing.

In 1852, two new pieces from Verne appeared in the Musée des familles: Martin Paz, a novella set in Lima which Verne wrote in 1851 and was published 10 July through 11 August 1852, and Les Châteaux en Californie, ou, Pierre qui roule n’amasse pas mousse (The Castles in California, or, A Rolling Stone Gathers No Moss), a one-act comedy full of racy double entendres.

In April and May 1854, the magazine published Verne’s short story Master Zacharius, an E. T. A. Hoffmann-like fantasy featuring a sharp condemnation of scientific hubris and ambition, followed soon afterward by A Winter Amid the Ice, a polar adventure story whose themes closely anticipated many of Verne’s novels.

The Musée also published some nonfiction popular science articles which, though unsigned, are generally attributed to Verne. Verne’s work for the magazine was cut short in 1856 when he had a serious quarrel with Pitre-Chevalier and refused to continue contributing (a refusal he would maintain until 1863, when Pitre-Chevalier died, and the magazine went to new editorship).

While writing stories and articles for Pitre-Chevalier, Verne began to form the idea of inventing a new kind of novel, a “Roman de la Science” (“novel of science”), which would allow him to incorporate large amounts of the factual information he so enjoyed researching in the Bibliothèque.

He is said to have discussed the project with the elder Alexandre Dumas, who had tried something similar with an unfinished novel, Isaac Laquedem, and who enthusiastically encouraged Verne’s project.[55]

At the end of 1854, another outbreak of cholera led to the death of Jules Seveste, Verne’s employer at the Théâtre Lyrique and by then a good friend.

Though his contract only held him to a further year of service, Verne remained connected to the theater for several years after Seveste’s death, seeing additional productions to fruition. He also continued to write plays and musical comedies, most of which were not performed.

Marriage & Family Life

In May 1856, Verne traveled to Amiens to be the best man at the wedding of a Nantes friend, Auguste Lelarge, to an Amiens woman named Aimée du Fraysne de Viane. Verne was invited to stay with the bride’s family and took to them warmly, befriending the entire household.

He also found himself increasingly attracted to the bride’s sister, Honorine Anne Hébée Morel, a widow aged 26 with two young children. Hoping to find a secure source of income, as well as a chance to court Morel in earnest, he jumped at her brother’s offer to go into business with a broker.

Verne’s father was initially dubious but gave in to his son’s requests for approval in November 1856. With his financial situation finally looking promising, Verne won the favor of Morel and her family and the couple were married on 10 January 1857.

Verne plunged into his new business obligations, leaving his work at the Théâtre Lyrique and taking up a full-time job as an agent de change on the Paris Bourse, where he became the associate of the broker Fernand Eggly.

Verne woke up early each morning so that he would have time to write, before going to the Bourse for the day’s work and in the rest of his spare time, he continued to consort with the Onze-Sans-Femme club (all eleven of its “bachelors” had by this time gotten married).

He also continued to frequent the Bibliothèque to do scientific and historical research, much of which he copied onto notecards for future use—a system he would continue for the rest of his life.

In July 1858, Verne and Aristide Hignard seized an opportunity offered by Hignard’s brother: a sea voyage, at no charge, from Bordeaux to Liverpool and Scotland.

It was Verne’s first trip outside France and deeply impressed him, and upon his return to Paris he fictionalized his recollections to form the backbone of a semi-autobiographical novel, Backwards to Britain (written in the autumn and winter of 1859–1860 and not published until 1989).

A second complimentary voyage in 1861 took Hignard and Verne to Stockholm from where they traveled to Christiania and through Telemark. Verne left Hignard in Denmark to return in haste to Paris, but missed the birth on 3 August 1861 of his only biological son, Michel.

Meanwhile, Verne continued work on the idea of a “Roman de la Science”, which he developed in a rough draft, inspired, according to his recollections, by his “love for maps and the great explorers of the world”. It took shape as a story of travel across Africa and would eventually become his first published novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon.

Collaboration with Hetzel

In 1862, through their mutual acquaintance Alfred de Bréhat, Verne came into contact with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetze, and submitted to him the manuscript of his developing novel, then called Voyage en Ballon.

Hetzel, already the publisher of Honoré de Balzac, George Sand, Victor Hugo and other well-known authors had long been planning to launch a high-quality family magazine in which entertaining fiction would combine with scientific education.

He saw Verne with his demonstrated inclination toward scrupulously researched adventure stories as an ideal contributor for such a magazine and accepted the novel, giving Verne suggestions for improvement.

Verne made the proposed revisions within two weeks and returned to Hetzel with the final draft, now titled Five Weeks in a Balloon. It was published by Hetzel on 31 January 1863.

To secure his services for the planned magazine, the Magasin d’Éducation et de Récréation (Magazine of Education and Recreation), Hetzel also drew up a long-term contract in which Verne would give him three volumes of text per year, each of which Hetzel would buy outright for a flat fee.

Verne having found both a steady salary and a sure outlet for writing at last, accepted immediately.

For the rest of his lifetime, most of his novels would be serialized in Hetzel’s Magasin before their appearance in book form, beginning with his second novel for Hetzel, The Adventures of Captain Hatteras (1864–65).

When The Adventures of Captain Hatteras was published in book form in 1866, Hetzel publicly announced his literary and educational ambitions for Verne’s novels by saying in a preface that Verne’s works would form a novel sequence called the Voyages extraordinaires (Extraordinary Voyages or Extraordinary Journeys).

Verne’s aim was “to outline all the geographical, geological, physical, and astronomical knowledge amassed by modern science and to recount, in an entertaining and picturesque format that is his own, the history of the universe”.

Late in life, Verne confirmed that this commission had become the running theme of his novels: “My object has been to depict the earth, and not the earth alone, but the universe… And I have tried at the same time to realize a very high ideal of beauty of style. It is said that there can’t be any style in a novel of adventure, but it isn’t true.”

However, he also noted that the project was extremely ambitious: “Yes! But the Earth is very large, and life is very short! In order to leave a completed work behind, one would need to live to be at least 100 years old!”

Hetzel influenced many of Verne’s novels directly, especially in the first few years of their collaboration, for Verne was initially so happy to find a publisher and he agreed to almost all of the changes Hetzel suggested.

Hetzel also rejected Verne’s next submission, Paris in the Twentieth Century, believing its pessimistic view of the future and its condemnation of technological progress were too subversive for a family magazine.

The relationship between publisher and writer changed significantly around 1869 when Verne and Hetzel were brought into conflict over the manuscript for Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas.

Verne had initially conceived of the submariner Captain Nemo as a Polish scientist whose acts of vengeance were directed against the Russians who had killed his family during the January Uprising.

Hetzel, not wanting to alienate the lucrative Russian market for Verne’s books, demanded that Nemo be made an enemy of the slave trade, a situation that would make him an unambiguous hero.

Verne, after fighting vehemently against the change, finally invented a compromise in which Nemo’s past is left mysterious. After this disagreement, Verne became notably cooler in his dealings with Hetzel, taking suggestions into consideration but often rejecting them outright.

From that point, Verne published two or more volumes a year. The most successful of these are: Voyage au centre de la Terre (Journey to the Center of the Earth, 1864); De la Terre à la Lune (From the Earth to the Moon, 1865); Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, 1869); and Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (Around the World in Eighty Days, 1872).

Verne could now live on his writings, but most of his wealth came from the stage adaptations of Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (1874) and Michel Strogoff (1876), which he wrote with Adolphe d’Ennery.

In 1867, Verne bought a small boat, the Saint-Michel, which he successively replaced with the Saint-Michel II and the Saint-Michel III as his financial situation improved. On board the Saint-Michel III, he sailed around Europe.

After his first novel, most of his stories were first serialised in the Magazine d’Éducation et de Récréation, a Hetzel biweekly publication, before being published in book form.

His brother Paul contributed to 40th French climbing of the Mont-Blanc and a collection of short stories – Doctor Ox – in 1874. Verne became wealthy and famous.

Meanwhile, Michel Verne married an actress against his father’s wishes, had two children by an underage mistress and buried himself in debts.The relationship between father and son improved as Michel grew older.

Later Years

Though he was raised Catholic, Verne became a deist in his later years, from about 1870 onward. Some scholars believe his deist philosophy is reflected in his novels, as they often involve the notion of God or divine providence but rarely mention the concept of Christ.

On 9 March 1886, as Verne was coming home, his twenty-six-year-old nephew, Gaston, shot at him twice with a pistol. The first bullet missed, but the second one entered Verne’s left leg, giving him a permanent limp that could not be overcome. This incident was hushed up in the media, but Gaston spent the rest of his life in a mental asylum.

After the death of both his mother and Hetzel, Jules Verne began publishing darker works. In 1888, Verne entered politics and was elected town councilor of Amiens, where he championed several improvements and served for fifteen years.

Verne was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur in 1870 and was then promoted to an Officier de la Légion d’honneur in 1892.

Death

On 24 March 1905, while ill with diabetes, Verne died at his home in Amiens, 44 Boulevard Longueville (now Boulevard Jules-Verne). His son, Michel, oversaw the publication of the novels Invasion of the Sea and The Lighthouse at the End of the World after Jules’s death.

The Voyages extraordinaires series continued for several years afterwards at the same rate of two volumes a year. It was later discovered that Michel Verne had made extensive changes in these stories and the original versions were eventually published at the end of the 20th century by the Jules Verne Society (Société Jules Verne).