*This post contains affiliate links which means that should you decide to make a purchase I may earn a small comission at no additional cost to you*

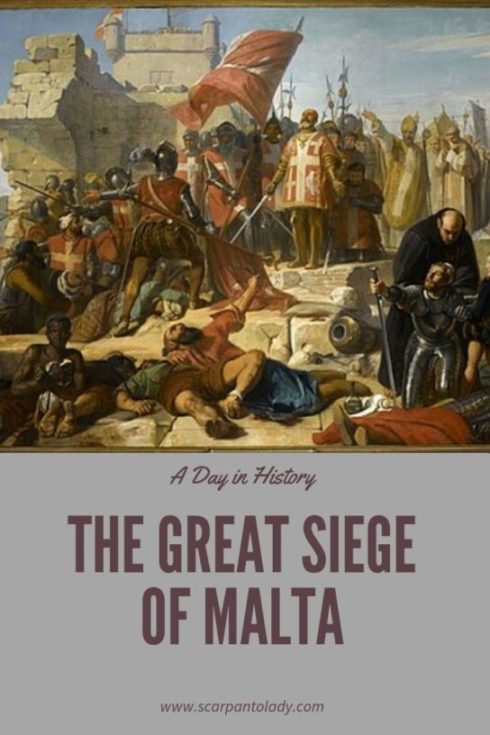

September 11 marks the 454th anniversary of the retreat of the Ottoman forces from Malta and the ending of the Great Siege. And what better way to celebrate one of the most famous events of the sixteenth-century Europe than to take a closer look at it?

Before The Siege

Following the six-month Siege of Rhodes in 1523 the Ottoman Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, had successfully managed to eject the Knights from their base. For seven years (1523-1530) the Knights of the Order of Saint John lacked a permanent base.

The Order soon made their naval base in the island of Malta when, on 26 October 1530 , the Grand Master of the Knights Philippe de Villiers de L’Isle-Adam with his followers sailed to Malta’s Grand Harbour to lay claim to Malta and Gozo (granted to them by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in exchange for one falcon sent annually to the Viceroy of Sicily and a solemn Mass to be celebrated on All Saints Day).

Malta’s position in the centre of the Mediterranean made it a strategically crucial gateway between East and West, especially as the Barbary pirates increased their forays into the western Mediterranean throughout the 1540s and 1550s.

In 1551 Dragut and the Ottoman admiral Sinan Pasha decided to take Malta and invaded the island with a force of about 10,000 men. After only a few days, however, Dragut broke off the siege and moved to the neighboring island of Gozo, where he bombarded the Cittadella for several days. The Knights’ governor on Gozo, Gelatian de Sessa, having decided that resistance was futile, threw open the doors to the Cittadella.

The corsairs sacked the town and took virtually the entire population of Gozo (approximately 5,000 people) into captivity. Dragut and Sinan then sailed south to Tripoli, where they soon seized the Knight’s garrison there.

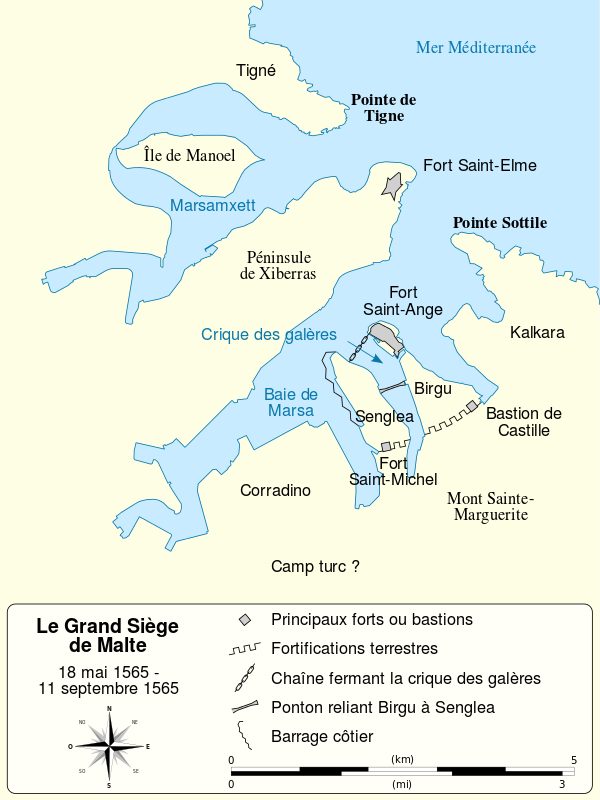

Expecting another Ottoman invasion within a year, Grand Master of the Knights Juan de Homedes ordered the strengthening of Fort Saint Angelo at the tip of Birgu (now Vittoriosa), as well as the construction of two new forts, Fort Saint Michael on the Senglea promontory and Fort Saint Elmo at the seaward end of Mount Sciberras (now Valletta)

By 1559 Dragut was causing the Christian powers such distress, even raiding the coasts of Spain, that Philip II of Spain organized the largest naval expedition in fifty years to evict the corsair from Tripoli. The Knights joined the expedition, which consisted of about 54 galleys and 14,000 men.

The ill-fated campaign climaxed in the Battle of Djerba in May 1560 when Ottoman admiral Piali Pasha surprised the Christian fleet off the Tunisian island of Djerba, capturing or sinking about half the Christian ships. The battle was disastrous for the Christians and marked the high point of Ottoman domination in the Mediterranean.

Getting Closer to the Siege

After the Battle of Djerba a Turkish attack at Malta was highly anticipated due to Malta’s strategic importance to the Ottoman plan of conquering more parts of Europe including Malta’s stepping stone Sicily and then the Kingdom of Naples.

In August 1560, Jean de Valette sent an order to all the Order’s priories that their knights prepare to return to Malta as soon as a citazione (summons) was issued. The Turks made a strategic error in not attacking at once, while the Spanish fleet lay in ruins, as the five-year delay allowed Spain to rebuild their forces.

In mid-1564 on of the Order’s most notorious naval commanders, Mathurin Romegas, captured several large merchantmen and took numerous high-ranking prisoners, including the governors of Cairo and Alexandria. Romegas‘ exploits made Sultan Suleiman seek the Order’s complete destruction.

By 1565 Jean de Valette’s spy network in Constantinople had informed him that the invasion was imminent. De Valette set about raising troops in Italy, laying in stores and finishing work on Fort Saint Angelo, Fort Saint Michael, and Fort Saint Elmo.

The Two Opposing Armies

Both of the following accounts are given by the Italian merceneray and official Order’s historian Francisco Balbi di Correggio

The Order’s Forces consisted of:

- 500 Knights Hospitaller

- 400 Spanish soldiers

- 800 Italian soldiers

- 500 soldiers from the galleys (Spanish Empire)

- 200 Greek and Sicilian soldiers

- 100 soldiers of the garrison of Fort St. Elmo

- 100 servants of the knights

- 500 galley slaves

- 3,000 soldiers drawn from the Maltese population

Total: 6.100

The Ottoman Forces consisted of:

- 6,000 Spahis (cavalry)

- 500 Spahis from Karamania

- 6,000 Janissaries

- 400 adventurers from Mytiline

- 2,500 Spahis from Rumelia

- 3,500 adventurers from Rumelia

- 4,000 “religious servants”

- 6,000 other volunteers

- Various corsairs from Tripoli and Algiers

Total: 28,500 from the East, 40,000 in all

The Siege

Ottoman Arrival

Before the arrival of the Turks Grand Master de Valette ordered the harvesting of all the crops, including unripened grain, to deprive the enemy of any local food supplies. Furthermore, the Knights poisoned all wells with bitter herbs and dead animals.

The Turkish armada arrived at dawn on Friday, 18 May, but did not land at once. On May 19 the first attack broke out. The following day the Ottoman fleet sailed up the southern coast of the island, turned around and finally anchored at Marsaxlokk (Marsa Sirocco) Bay, nearly 6.2 miles from the Grand harbour region. According to many accounts, Balbi’s in particular, a dispute arose between the leader of the land forces, the 4th Vizier serdar Kızılahmedli Mustafa Pasha, and the supreme naval commander, Piali Pasha , about where to anchor the fleet. Piali wished to shelter it at Marsamxett Harbour in order to avoid the sirocco and be near the Grand Harbour but Mustafa disagreed, because to anchor the fleet there would require the reducing Fort St. Elmo, (which guarded the entrance to the harbour) first.

Mustafa intended, according to these accounts, to attack the poorly defended former capital Mdina (standing in the centre of the island) then attack Forts St. Angelo and Michael by land. If so, an attack on Fort St. Elmo would have been entirely unnecessary. Nevertheless, Mustafa relented, believing that only a few days would be necessary to destroy St. Elmo. After the Turks were able to emplace their guns, at the end of May they commenced a bombardment.

While the Ottomans were landing, the knights and Maltese made some last-minute improvements to the defences of Birgu and Senglea. The Ottomans set up their main camp in Marsa, which was close to the Knights’ fortifications followed by camps on Saint Margherita Hill and Sciberra’s Peninsula in the next days.

Capture of Fort Saint Elmo

Having correctly calculated that the Turks would thus begin the campaign by attempting to capture Fort St Elmo, de Valette sent reinforcements and concentrated half of his heavy artillery within the fort. His intent was for them to hold out for a relief promised by Don Garcia, Viceroy of Sicily. The unremitting bombardment of the fort began on 27 May by three dozen guns on the higher ground of Mt. Sciberras. The fort was reduced to rubble within a week, but de Valette evacuated the wounded nightly and resupplied the fort from across the harbour. After Dragut’s arrival new batteries were set up to imperil the ferry lifeline. On 3 June, a party of Jannisaries managed to seize the fort’s ravelin and ditch. Still, by 8 June, the Knights sent a message to the Grand Master that the Fort could no longer be held but were rebuffed with messages that St Elmo must hold until the reinforcements arrived.

The Turks attacked the damaged walls on June 10 and 15, and made an all out assault on June 16, during which even the slave and hired galley oarsmen housed in St Elmo, as well as the native Maltese soldiers, reportedly fought and died “almost as bravely as the Knights themselves.” Two days later, Dragut was seen in a trench cannon emplacement arguing with the Turkish gunners about their level of fire. At Dragut’s insistence a cannon’s aim was lowered, but the aim was too low, and when fired its ball detached part of the trench which hit Dragut in the head, killing him.

Finally, on 23 June, the Turks seized what was left of Fort St. Elmo. They killed all the defenders, totaling over 1,500 men, but spared nine Knights whom the Corsairs had captured. A small number of Maltese, managed to escape by swimming across the harbour.

Mustafa had the bodies of the knights decapitated and their bodies floated across the bay on mock crucifixes. In response, de Valette beheaded all his Turkish prisoners, loaded their heads into his cannons and fired them into the Turkish camp

Although the Turks did succeed in capturing St. Elmo, allowing Piali to anchor his fleet in Marsamxett, the siege of Fort St. Elmo had cost the Turks at least 6,000 men, including half of their Janissaries.

The Senglea Peninsula

On 15 July, Mustafa ordered a double attack against the Senglea peninsula. He had transported 100 small vessels across Mt. Sciberras to the Grand Harbour, in order to launch a sea attack against the promontory using about 1,000 Janissaries, while the Corsairs attacked Fort St. Michael on the landward end. Luckily for the Maltese, a defector warned de Valette about the impending strategy and the Grand Master had time to construct a palisade along the Senglea promontory, which successfully helped to deflect the attack. Just all but one of the vessels sank, killing or drowning over 800 of the attackers. The land attack failed simultaneously when relief forces were able to cross to Ft. St. Michael across a floating bridge, with the result that Malta was saved for the day.

Mustafa ordered another massive double assault on 7 August, this time against Fort St. Michael and Birgu itself. On this occasion, the Turks breached the town walls and it seemed that the siege was over, but unexpectedly the invaders retreated. As it happened, the cavalry commander Captain Vincenzo Anastagi, on his daily sortie from Mdina, had attacked the unprotected Turkish field hospital, killing everyone. The Turks, thinking the Christian relief had arrived from Sicily, broke off their assault.

St Michael and Birgu

After the attack of 7 August, the Turks resumed their bombardment of St. Michael and Birgu, with at least one other major assault against the town between 19–21 August. The actual events that happened during those days are not entirely clear.

Balbi, in his diary entry for 20 August, says only that de Valette was told the Turks were within the walls and the Grand Master ran to “the threatened post where his presence worked wonders. Sword in hand, he remained at the most dangerous place until the Turks retired.”

Fort St. Michael and Mdina

At some point in August, the Council of Elders decided to abandon the town and retreat to Fort St. Angelo. De Valette, however, refused this proposal. Although the bombardment and minor assaults continued, the invaders were stricken by an increasing desperation. Towards the end of August, the Turks attempted to take Fort St. Michael two times: first with the help of a manta ( a small siege engine covered with shields) and then by use of a full-blown siege tower. In both cases, Maltese engineers tunneled out through the rubble and destroyed the constructions with point-blank salvos of chain shot.

At the beginning of September, the weather’s turning had Mustafa order a march on Mdina, intending to winter there. However the occurance of the attack failed. The poorly-defended and supplied city deliberately started firing its cannon at the approaching Turks at pointlessly long range. This bluff scared them away by fooling the already demoralised Turks into thinking the city had ammunition to spare.

By 8 September, the Turks had embarked their artillery and were preparing to leave the island, having lost perhaps a third of their men to fighting and disease.

Gran Soccorso

On 7 September, Don Garcia had at last landed with about 8,000 men at St. Paul’s Bay on the north end of the island. The relief force consisted of mainly Spanish and Italian soldiers, sent by the Spanish Empire as well as the Duchy of Florence, the Republic of Genoa, the Papal States and the Duchy of Savoy.

The so-called Grande Soccorso positioned themselves on the ridge of San Pawl tat-Tarġa, waiting for the retreating Turks. It is said that when some hot-headed knights of the relief force saw the Turkish retreat and the burning villages in its wake, they charged without waiting for orders from Ascanio della Corgna. Della Corgna had no choice but to order a general charge which resulted in the massacre of the retreating Turkish force. The Turks fled to their ships and from the islands on 11 September.

Aftermath

Malta had survived the Turkish assault, and throughout Europe people celebrated what would turn out to be the last epic battle involving Crusader Knights.

Jean de Valette, Grand Master of the Knights of Malta, had a key influence in the victory against Ottomans. He had a major impact, by bringing together the kings of Europe in an alliance against the previously seemingly invincible Ottomans.

Such was the gratitude of Europe for the knights’ heroic defense that money soon began pouring into the island, allowing de Valette to construct a fortified city, Valletta, on Mt. Sciberras. de Valette didn’t leave to see Valletta completed as he died in 1568. He was buried in the Crypt of the Conventual Church of the Order within Valletta’s walls.

If you are interested in learning more about the Siege of Malta you should check out Francisco Balbi di Corregio’s journal