Family history & Early life

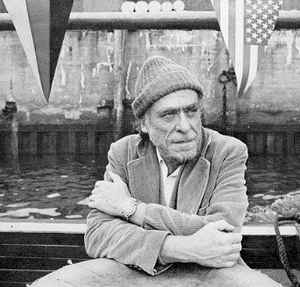

Charles Bukowski was born Heinrich Karl Bukowski in Andernach, Rhine Province to Heinrich Bukowski and Katharina (née Fett).

His paternal grandfather Leonard Bukowski had moved to the United States from the German Empire in the 1880s. In Cleveland, Leonard met Emilie Krause, an ethnic German, who had emigrated from Danzig, Prussia. They married and settled in Pasadena.

His mother, Katharina Bukowski, was the daughter of Wilhelm Fett and Nannette Israel.

Bukowski’s parents met in Andernach, Germany, following World War I. His father was German-American and a sergeant in the United States Army serving in Germany after Germany’s defeat in 1918. He had an affair with Katharina, a German friend’s sister, and she became pregnant. Charles Bukowski repeatedly claimed to be born out of wedlock, but Andernach marital records indicate that his parents married one month before his birth.

Afterwards Heinrich Bukowski became a building contractor, set to make great financial gains in the aftermath of the war, and after two years moved the family to Pfaffendorf. Heinrich was unable to make a living, so he decided to move the family to the United States. On April 23, 1923, they sailed from Bremerhaven to Baltimore, Maryland, where they settled.

The family moved to Mid-City, Los Angeles, US in 1930, the city where Charles Bukowski’s father and grandfather had previously worked and lived. Young Charles spoke English with a strong German accent and was taunted by his childhood playmates with the epithet “Heini” in his early youth.

In the 1930s Charles Bukowski’s father was often unemployed. In the autobiographical Ham on Rye, Charles Bukowski says that, with his mother’s acquiescence, his father was frequently abusive, both physically and mentally, beating his son for the smallest imagined offense.

During his youth Bukowski was shy and socially withdrawn, a condition exacerbated during his teen years by an extreme case of acne. Neighborhood children ridiculed his German accent and the clothing his parents made him wear. The depression bolstered his rage as he grew and gave him much of his voice and material for his writings.

In his early teen years, Bukowski had an epiphany when he was introduced to alcohol by his loyal friend William “Baldy” Mullinax, depicted as “Eli LaCrosse” in Ham on Rye, son of an alcoholic surgeon. “This [alcohol] is going to help me for a very long time,” he later wrote, describing drinking as a method he could use to come to more amicable terms with his own life.

After graduating from Los Angeles High School, Bukowski attended Los Angeles City College for two years, where he took courses in art, journalism, and literature, before quitting at the start of World War II. He then moved to New York to begin a career as a financially pinched blue-collar worker with dreams of becoming a writer.

On July 22, 1944 Bukowski was arrested by F.B.I. agents in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he lived at the time, on suspicion of draft evasion. At a time when the United States was at war with Germany and many Germans and German-Americans in the United States were suspected of disloyalty, his German birth troubled the US authorities. He was held for 17 days in Philadelphia’s Moyamensing Prison. Sixteen days later, he failed a psychological examination that was part of his mandatory military entrance physical test and was given a Selective Service Classification of 4-F (unfit for military service).

Early writing career

When Bukowski was 24 his short story “Aftermath of a Lengthy Rejection Slip” was published in Story magazine. Two years later another short story, “20 Tanks from Kasseldown”, was published by the Black Sun Press in Issue III of Portfolio: An Intercontinental Quarterly, a limited-run, loose-leaf broadside collection printed in 1946 and edited by Caresse Crosby.

Failing to break into the literary world, Bukowski grew disillusioned with the publication process and quit writing for almost a decade, a time that he referred to as a “ten-year drunk”. These “lost years” formed the basis for his later semiautobiographical chronicles along with fictionalized versions of Bukowski’s life through his highly stylized alter-ego, Henry Chinaski.

During part of this period he continued living in Los Angeles, working at a pickle factory for a short time but also spending some time roaming about the United States, working sporadically and staying in cheap rooming houses.

In the early 1950s Bukowski took a job as a fill-in letter carrier with the United States Post Office Department in Los Angeles, but resigned just before he reached three years’ service.

In 1955 he was treated for a near-fatal bleeding ulcer. After leaving the hospital he began to write poetry. In 1955 he agreed to marry Barbara Frye, a small-town Texas poet, but they divorced in 1958. According to Howard Sounes‘s Charles Bukowski: Locked in the Arms of a Crazy Life, she later died under mysterious circumstances in India. Following his divorce Bukowski resumed drinking and continued writing poetry.

Several of his poems were published in the late 1950s in Gallows, a small poetry magazine published briefly (the magazine lasted for two issues) by Jon Griffith.

The small avant-garde literary magazine Nomad, published by Anthony Linick and Donald Factor, offered a home to Bukowski’s early work. Nomad‘s inaugural issue in 1959 featured two of his poems. A year later, Nomad published one of Bukowski’s best known essays, Manifesto: A Call for Our Own Critics.

During the 1960s

By 1960, Bukowski had returned to the post office in Los Angeles where he began work as a letter filing clerk, a position he held for more than a decade. In 1962, he was distraught over the death of Jane Cooney Baker, his first serious girlfriend. Bukowski turned his inner devastation into a series of poems and stories lamenting her death.

In 1964 a daughter, Marina Louise Bukowski, was born to Bukowski and his live-in girlfriend Frances Smith, whom he referred to as a “white-haired hippie”, “shack-job”, and “old snaggle-tooth”.

E.V. Griffith, editor of Hearse Press, published Bukowski’s first separately printed publication, a broadside titled “His Wife, the Painter,” in June 1960. This event was followed by Hearse Press’s publication of “Flower, Fist and Bestial Wail”, Bukowski’s first chapbook of poems in October, 1960.

“His Wife, the Painter” and three other broadsides (“The Paper on the Floor”, “The Old Man on the Corner” and “Waste Basket”) formed the centerpiece of Hearse Press’s “Coffin 1,” an innovative small-poetry publication consisting of a pocketed folder containing 42 broadsides and lithographs which was published in 1964. Hearse Press continued to publish poems by Bukowski through the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s.

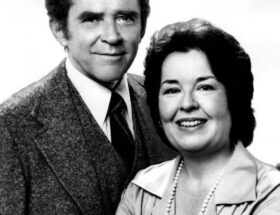

Jon and Louise Webb, publishers of The Outsider literary magazine, featured some of Bukowski’s poetry in its pages. Under the Loujon Press imprint, the Webbs published Bukowski’s ”It Catches My Heart in Its Hands” in 1963 and ”Crucifix” in a Deathhand in 1965.

Beginning in 1967 Bukowski wrote the column “Notes of a Dirty Old Man” for Los Angeles’ Open City, an underground newspaper. When Open City was shut down in 1969, the column was picked up by the Los Angeles Free Press as well as the hippie underground paper NOLA Express in New Orleans.

In 1969 Bukowski and Neeli Cherkovski launched their own short-lived mimeographed literary magazine, Laugh Literary and Man the Humping Guns. They produced three issues over the next two years.

Working with Black Sparrow Press

In 1969 Bukowski accepted an offer from legendary Black Sparrow Press publisher John Martin and quit his post office job to dedicate himself to full-time writing. As he explained in a letter at the time, “I have one of two choices – stay in the post office and go crazy … or stay out here and play at writer and starve. I have decided to starve.”

Less than one month after leaving the postal service he finished his first novel, Post Office. As a measure of respect for Martin’s financial support and faith in a relatively unknown writer, Bukowski published almost all of his subsequent major works with Black Sparrow Press, which became a highly successful enterprise owing to Martin’s business acumen and editorial skills. An avid supporter of small independent presses, Bukowski continued to submit poems and short stories to innumerable small publications throughout his career.

Bukowski embarked on a series of love affairs and one-night trysts. One of these relationships was with Linda King, a poet and sculptress. His other affairs were with a recording executive and a twenty-three-year-old redhead; he wrote a book of poetry as a tribute to his love for the latter, titled, “Scarlet” (Black Sparrow Press, 1976). His various affairs and relationships provided material for his stories and poems.

Another important relationship was with “Tanya”, pseudonym of Amber O’Neil, described in Bukowski’s “Women” as a pen-pal that evolved into a week-end tryst at Bukowski’s residence in Los Angeles in the 1970s. Amber O’Neil later self-published a chapbook about the affair entitled “Blowing My Hero”.

In 1976, Bukowski met Linda Lee Beighle, a health food restaurant owner, rock-and-roll groupie, aspiring actress, heiress to a small Philadelphia “Main Line” fortune and devotee of Meher Baba. Two years later Bukowski moved from the East Hollywood area, where he had lived for most of his life, to the harborside community of San Pedro, the southernmost district of the City of Los Angeles.

Beighle followed him and they lived together intermittently over the next two years. They were eventually married by Manly Palmer Hall, a Canadian-born author, mystic, and spiritual teacher in 1985. Beighle is referred to as “Sara” in Bukowski’s novels Women and Hollywood.

In May 1978, he returned to Germany and gave a live poetry reading of his work before an audience in Hamburg. His last international performance was in October 1979 in Vancouver, British Columbia. It was released on DVD as There’s Gonna Be a God Damn Riot in Here.

In March 1980 he gave his last reading at the Sweetwater club in Redondo Beach, which was released as Hostage on audio CD and The Last Straw on DVD. In 2010 the unedited versions of both The Last Straw and Riot were released as One Tough Mother on DVD.

In the 1980s, he collaborated with illustrator Robert Crumb on a series of comic books, with Bukowski supplying the writing and Crumb providing the artwork.

Death

Bukowski died of leukemia on March 9, 1994, in San Pedro, shortly after completing his last novel, Pulp. The funeral rites, orchestrated by his widow, were conducted by Buddhist monks. He is interred at Green Hills Memorial Park in Rancho Palos Verdes. An account of the proceedings can be found in Gerald Locklin‘s book Charles Bukowski: A Sure Bet.

His gravestone reads: “Don’t Try”, a phrase which Bukowski uses in one of his poems, advising aspiring writers and poets about inspiration and creativity.

Bukowski explained the phrase in a 1963 letter to John William Corrington: “Somebody at one of these places […] asked me: ‘What do you do? How do you write, create?’ You don’t, I told them. You don’t try. That’s very important: not to try, either for Cadillacs, creation or immortality. You wait, and if nothing happens, you wait some more. It’s like a bug high on the wall. You wait for it to come to you. When it gets close enough you reach out, slap out and kill it. Or, if you like its looks, you make a pet out of it.”