Early life

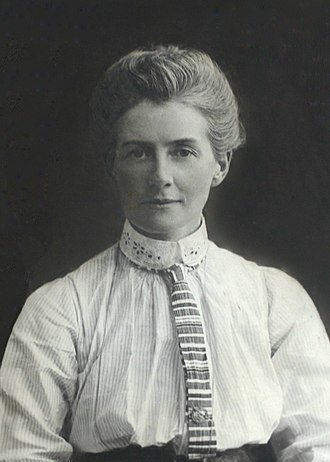

Edith Louisa Cavell was born on 4 December 1865 in Swardeston, a village near Norwich, where her father was vicar for 45 years. She was the eldest of the four children of the Reverend Frederick Cavell and his wife Louisa Sophia Warming. Edith’s siblings were Florence Mary (b. 1867), Mary Lilian (b. 1870) and John Frederick Scott (b.1872).

She was educated at Norwich High School for Girls and then at boarding schools in Clevedon, Somerset and Peterborough (Laurel Court).

After a period as a governess, she returned home to care for her father during a serious illness. The experience led her to become a nurse after her father’s recovery.

In April 1896, Edith applied to become a nurse probationer at the London Hospital under Matron Eva Luckes. She worked in various hospitals in England, including Shoreditch Infirmary (since renamed St Leonard’s Hospital). As a private travelling nurse treating patients in their homes, Edith travelled to tend patients with cancer, gout, pneumonia, pleurisy, eye issues and appendicitis.

She was sent to assist with the typhoid outbreak in Maidstone during 1897. Along with other staff she was awarded the Maidstone Medal.

In 1906 Edith took a temporary post as matron of the Manchester and Salford Sick and Poor and Private Nursing Institution and worked there for about nine months. While there she worshipped at Sacred Trinity Church on Chapel Street, Salford and her name is included on the church war memorial.

In 1907, she was recruited by Antoine Depage to be matron of a newly established nursing school, L’École Belge d’Infirmières Diplômées (or the Berkendael Medical Institute) on the Rue de la Culture, in Ixelles, Brussels.

By 1910, Edith felt “that the profession of nursing had gained sufficient foothold in Belgium to warrant the publishing of a professional journal” and she launched the nursing journal, L’infirmière. Within a year, she was training nurses for three hospitals, twenty-four schools, and thirteen kindergartens in Belgium.

When the First World War broke out, she was visiting her widowed mother in Norfolk. She returned to Brussels, where her clinic and nursing school were taken over by the Red Cross.

First World War

In November 1914, after the German occupation of Brussels, Edith began sheltering British soldiers and funnelling them out of occupied Belgium to the neutral Netherlands. Wounded British and French soldiers as well as Belgian and French civilians of military age were hidden from the Germans and provided with false papers by Prince Réginald de Croÿ at his château of Bellignies near Mons.

From there, they were conducted by various guides to the houses of Edith, Louis Séverin and others in Brussels, where their hosts would furnish them with money to reach the Dutch frontier and provide them with guides obtained through Philippe Baucq.This placed Edith in violation of German military law, with German authorities becoming increasingly suspicious of her actions, which were further fuelled by her outspokenness.

Edith was arrested on 3 August 1915 and charged with harbouring Allied soldiers. She had been betrayed by Georges Gaston Quien, who was later convicted by a French court as a collaborator. She was held in Saint-Gilles prison for ten weeks, the last two of which were spent in solitary confinement.

Edith made three depositions to the German police (on 8, 18 and 22 August), admitting that she had been instrumental in conveying about 60 British and 15 French soldiers, as well as about 100 French and Belgian civilians of military age, to the frontier and had sheltered most of them in her house.

At her court-martial, she was prosecuted for aiding British and French soldiers, in addition to young Belgian men, to cross the Dutch border and eventually enter Britain. She admitted her guilt when she signed a statement the day before the trial.

Edith declared that the soldiers she had helped escape thanked her in writing when they arrived safely in Britain. This admission confirmed that she had helped the soldiers navigate the Dutch frontier, but it also established that she helped them escape to a country at war with Germany. Her fellow defendants included Prince Reginald’s sister, Princess Marie of Croÿ.

The penalty, according to German military law, was death. Paragraph 58 of the German Military Code determined that “at time of war, anyone who with the intention of aiding a hostile power, or of causing harm to the German or allied troops” commits any of the crimes defined in paragraph 90 of the German Penal Code “shall be punished with death for war treason”.

Specifically, Edith was charged under paragraph 90 (1) no. 3 Reichsstrafgesetzbuch, for “conveying troops to the enemy”, a crime normally punishable by life imprisonment in peacetime. It was possible to charge Edith with war treason as paragraph 160 of the German Military Code extended application of paragraph 58 to foreigners “present in the zone of war”.

While the First Geneva Convention ordinarily guaranteed protection of medical personnel, that protection was forfeit if used as cover for any belligerent action. This forfeiture is expressed in article 7 of the 1906 version of the Convention, which was the version in force at the time and justified prosecution on the basis of German law.

The British government could do nothing to help her. Sir Horace Rowland of the Foreign Office said: “I am afraid that it is likely to go hard with Miss Cavell; I am afraid we are powerless.”

Lord Robert Cecil, Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, advised that, “Any representation by us will do her more harm than good.”

The United States, however, had not yet joined the war and was in a position to apply diplomatic pressure. Hugh S. Gibson, Secretary to the U.S. Legation at Brussels, made clear to the German government that executing Edith would further harm Germany’s already damaged reputation.

Later, he wrote:

We reminded [German civil governor Baron von der Lancken] of the burning of Louvain and the sinking of the Lusitania, and told him that this murder would rank with those two affairs and would stir all civilized countries with horror and disgust. Count Harrach broke in at this with the rather irrelevant remark that he would rather see Miss Cavell shot than have harm come to the humblest German soldier, and his only regret was that they had not “three or four old English women to shoot.”

Baron von der Lancken is known to have stated that Edith should be pardoned because of her complete honesty and because she had helped save so many lives, German as well as Allied. However, General von Sauberzweig, the military governor of Brussels, ordered that “in the interests of the State” the implementation of the death penalty against Baucq and Cavell should be immediate, denying higher authorities an opportunity to consider clemency.

Edith was defended by lawyer Sadi Kirschen from Brussels. Of the twenty-seven defendants, five were condemned to death: Cavell, Baucq, Louise Thuliez, Séverin and Countess Jeanne de Belleville. Of those five sentenced to death, only Cavell and Baucq were executed, as the other three were granted reprieve.

Edith was arrested not for espionage, as many were led to believe, but for “war treason”, despite not being a German national. She may have been recruited by the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and turned away from her espionage duties in order to help Allied soldiers escape, although this is not widely accepted.

The former director-general of MI5, Stella Rimington, announced in 2015 that she had unearthed documents in Belgian military archives that confirmed an intelligence gathering aspect to Cavell‘s network. The BBC Radio 4 programme that presented Rimington’s quote, noted Edith‘s use of secret codes and, though amateurish, other network members’ successful transmission of intelligence.

When in custody, Edith was questioned in French, but her trial was minuted in German, which some assert gave the prosecutor the opportunity to misinterpret her answers. Although she may have been misrepresented, she made no attempt to defend herself, but responded to have channelled “environ deux cents” soldiers to the Dutch border.

She was provided with a defender approved by the German military governor, as the previous defender, who was chosen for Cavell by her assistant, Elizabeth Wilkins, was ultimately rejected by the governor.

Execution

The night before her execution, she told the Reverend H Stirling Gahan, the Anglican chaplain of Christ Church Brussels and former member of staff at Monkton Combe School who had been allowed to see her and to give her Holy Communion: “I am thankful to have had these ten weeks of quiet to get ready. Now I have had them and have been kindly treated here. I expected my sentence and I believe it was just. Standing as I do in view of God and Eternity, I realise that patriotism is not enough, I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

Her final words to the German Lutheran prison chaplain, Paul Le Seur, were recorded as: “Ask Father Gahan to tell my loved ones later on that my soul, as I believe, is safe, and that I am glad to die for my country.”

From his sick bed Brand Whitlock, the U.S. ambassador to Belgium, wrote a personal note on Edith‘s behalf to Moritz von Bissing, the Governor-General of Belgium. Hugh Gibson, the legal adviser to the United States legation and Rodrigo de Saavedra y Vinent, 2nd Marques de Villalobar, the Spanish minister, formed a midnight deputation of appeal for mercy or at least postponement of execution.

Despite these efforts, on 11 October, Baron von der Lancken allowed the execution to proceed.

Sixteen men, forming two firing squads, carried out the sentence pronounced on her and on four Belgian men at the Tir national shooting range in Schaerbeek, at 7:00 am on 12 October 1915. There are conflicting reports of the details of Edith‘s execution. However, according to the eyewitness account of the Reverend Le Seur, who attended Edith in her final hours, eight soldiers fired at her while the other eight executed Baucq.

Her execution, certification of death, and burial were all witnessed by the German poet Gottfried Benn in his capacity as a ‘Senior Doctor in the Brussels Government since the first days of the (German) occupation’. Benn wrote a detailed account titled “Wie Miss Cavell erschossen wurde” (How Miss Cavell was shot, 1928).

On instructions from the Spanish minister, Belgian women immediately buried her body next to Saint-Gilles Prison.

Burial

Edith‘s remains were returned to Britain after the war, sailing from Ostend aboard the destroyer HMS Rowena and landing at Admiralty Pier in Dover on 14 May 1919. She was one of only three sets of British remains repatriated following the end of the War, the others being Charles Fryatt and The Unknown Warrior.

As the ship arrived a full peal of Grandsire Triples (5040 Changes, Parker’s Twelve-Part) was rung on the bells of St Mary’s Church in the town. A plaque commemorating the peal in the church’s bell-ringing chamber states it was “Rung with the bells deeply muffled with the exception of the Tenor which was open at back stroke, in token of respect to Nurse Cavell”. All the ringers were former soldiers, including Frederick W Elliot, formerly King’s Royal Rifle Corps, who had been a prisoner of war in Germany for eight months.

Her body was transferred to a railway van and lay in state on the Pier overnight before departing from Dover Harbour station for London Victoria. Becoming known as the Cavell Van, that van is kept as a memorial on the Kent & East Sussex Railway and is usually open to view at Bodiam railway station.

From Victoria, Edith‘s body was processed to Westminster Abbey for a state funeral on 15 May, before finally being reburied at the east side of Norwich Cathedral on 19 May, where a graveside service is still held each October. The following year a stone memorial, including a statue of Cavell by George Frampton was unveiled near Trafalgar Square in London.